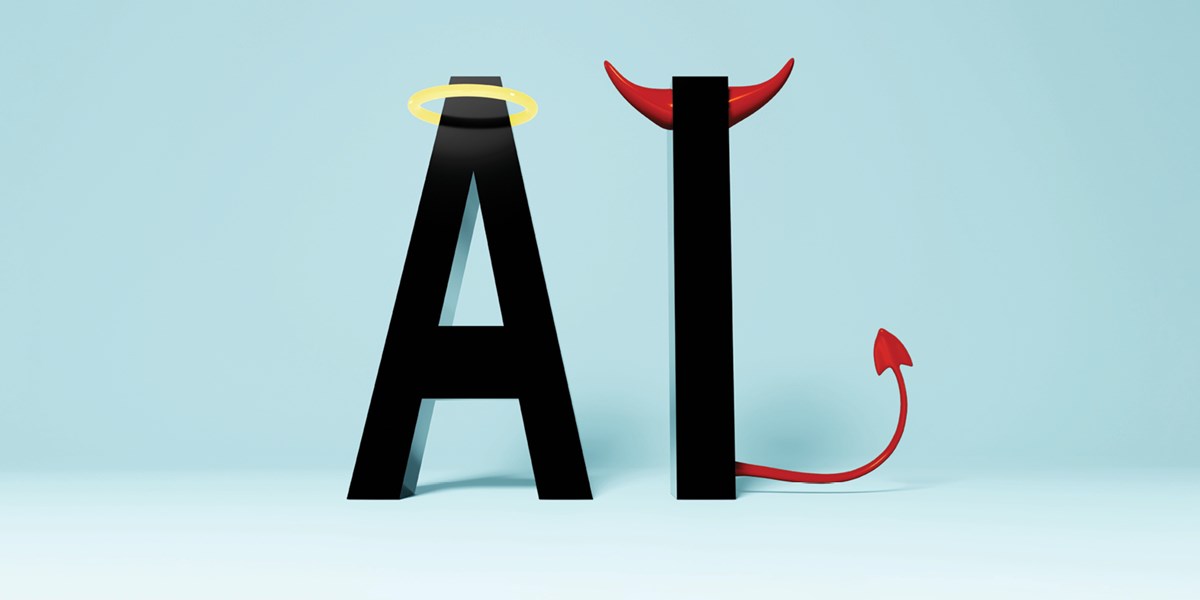

The jury’s still out on whether artificial intelligence will do more good than harm. UML experts address 11 of the most pressing questions about AI.

06/21/2024

By UML Magazine Staff

Things are changing so quickly in the world of artificial intelligence that by the time you read this, the computers may have already cured cancer and reversed climate change. Or, on the flip side, perhaps they’ve overthrown humanity and bred a society of killer robots.

If you’re like us, you’ve heard it all—and are likely sick of hearing about it. But for good or bad, AI isn’t going anywhere. In fact, its presence in every facet of our lives will continue to expand, say experts.

One of the most profound changes ahead, says UML alumnus and Android co-founder Rich Miner ’86, ’89, ’97, is that “there will be a revolution in the ways in which humans interact with computers.”

For instance, the development of new software is historically a complex and time-consuming process that required arcane skills, says Miner, an advisor at Google, where he spent many years helping lead Android development and then growing the company’s venture fund.

But now, he says, generative AI-based systems like ChatGPT can understand our written and spoken words, our drawings and, soon, our gestures and facial expressions.

“This means the computer can communicate using natural forms of communication that most of us learn at an early age,” says Miner, who is currently focused on his work as co-founder and advisor for a “stealth startup” based in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

“And from relatively straightforward conversational exchanges or written requirements, the computer can lever-age those large language models, or LLMs, and the ability to generate images and videos to do a huge amount of work on our behalf, producing quality work, including new computer programs. This will have a huge impact on how people are able to leverage computers in the future.”

It also brings to mind a question we raised in these pages eight years ago, when the cover story of UML Magazine was “Will Robots Rule the World?”

At the time, faculty experts like Computer Science Prof. Ben Liu warned that artificial intelligence would push the robot revolution to places that are difficult to even imagine.

“It’s hard to see where it’s going to hit the limit,” Liu said, “but for starters, it will replace more and more cognitive, white-collar work.” According to Pew Research Center, he was right: About one in five white collar jobs are ripe for AI takeover, its new study found.

Meanwhile, a few months ago, the “godfather” of AI, Geoffrey Hinton, warned in a “60 Minutes” interview that we have arrived at “a turning point for humanity” and that AI has the potential to one day take over.

That’s why it’s vital that we get ahead of it, says University of Massachusetts Chief Information Officer Mike Milligan, who was recently appointed co-chair of the state’s strategic AI task force by Gov. Maura Healey.

“Whether in the way we learn at universities, manage complex organizations or engage in our democracy, we are all going to need new skills and knowledge to use AI for positive purposes and protect ourselves from its potentially harmful effects,” says Milligan, a vice president for the system.

UMass Lowell is doing its part. The university launched its own AI task force this year, with an initial priority of creating policies for how students and faculty can most effectively use AI in learning and teaching. Faculty researchers across disciplines, meanwhile, are studying AI impacts and building new technologies. They’re using AI to speed up cancer detection and to reduce suicide rates of veterans; they’re researching the use of robotic pets to drive sales of consumer goods and incorporating AI tools to improve health care for older adults. Computer Science Assoc. Prof. Anna Rumshisky is spending half her time as a visiting scientist at Amazon, where she’s helping to build better natural language processing tools for the company’s Alexa tool.

And it’s not just faculty: We’re hearing from more and more alumni who are using AI for good—or being forced to adapt to it—in their jobs.

“It’s an exciting time,” says Holly Yanco, chair of the Miner School of Computer & Information Sciences (named for Rich Miner) and director of the New England Robotics Validation and Experimentation (NERVE) Center. “At UMass Lowell, a lot of us have been focusing on ways to use AI to help society. We’re making a positive impact on the world.”

Though AI opens the door to promising advances, it does have drawbacks, from biases in training data to the massive amount of energy needed to run server farms, says Yanco, who is a fellow of both the Association for the Advancement of Artificial Intelligence and the American Association for the Advancement of Science, honored by both organizations for her contributions to the field of human-robot interaction.

“Any technology has good and bad sides, but I’m optimistic about AI,” she says.

Here, experts in the UML community weigh in on 11 of the most pressing questions about AI.