Researchers Develop Techniques and Technologies to Monitor Water Quality and Safety

09/01/2024

By Madeline Bodin

Water is life.

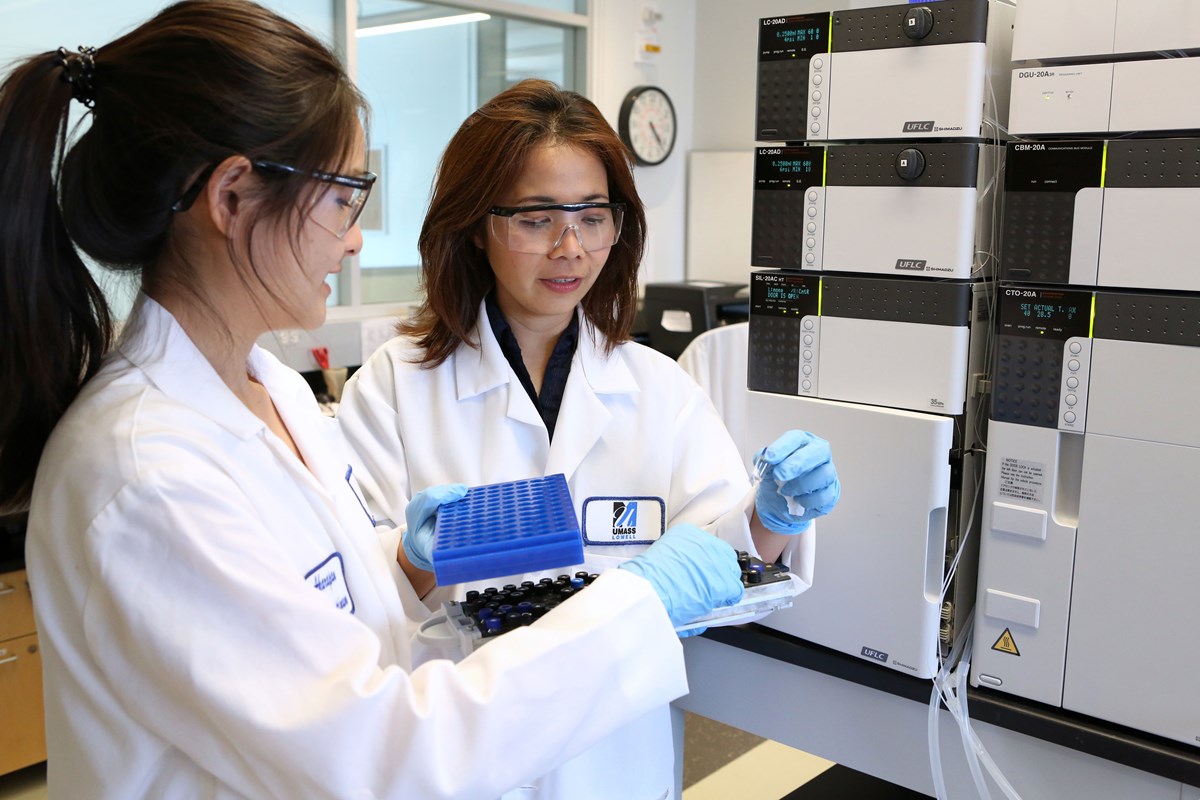

The health of our water supply both reflects and influences human health, and it has a major impact on our environment. Two Francis College of Engineering faculty members, Assoc. Prof. Sheree Pagsuyoin (civil and environmental engineering) and Prof. Yan Luo (electrical and computer engineering), are developing methods and technologies to test water for illicit drugs and pathogens that can impact public health and aquatic resources.

Pagsuyoin and Luo have recently won prestigious national awards and grants to advance their work. Pagsuyoin received a Fulbright Global Scholar Award and a National Science Foundation (NSF) CAREER Award, a significant early-career faculty development award.

The Fulbright scholarship has taken Pagsuyoin across the globe to explore how the extent of illicit drug use in a population can be revealed by analyzing the drugs’ residue in wastewater. She is currently collaborating with colleagues in Busan, South Korea; Manila, the Philippines; and Antwerp, Belgium. The project also includes her research in Lowell.

The four locations provide four different settings for Pagsuyoin’s work in terms of available technology, existing know-how, funding and cultural views of illicit drug use. Her colleagues in Busan have the technical background, the technology and the funding to perform the lab analysis. As in the United States, wastewater-based epidemiology—analyzing wastewater for the presence of harmful organisms such as SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19—is simply not as common in South Korea.

“[This research] is critical in safeguarding public health, particularly in vulnerable coastal areas that provide communities with food, recreation and protection from storms.” -Prof. Yan Luo

When she headed to Manila, Pagsuyoin brought her own lab equipment, which was lacking in the facility that she visited. For Pagsuyoin, it was a return to the city where she earned a bachelor’s degree in chemical engineering and a master’s degree in environmental engineering.

Among the four cities, the cultural differences were significant, Pagsuyoin says. “Here in Massachusetts, some drug use is legal. We might think of it as recreational. At worst, we think of drug use as a disease,” she says. “In South Korea and the Philippines, drug use is a criminal act. It’s a sensitive topic to discuss.”

European researchers have been leaders in using wastewater analysis to examine the extent of drug use in a population. Pagsuyoin sees her visit to Antwerp as an opportunity to learn from experienced scientists, as well as to share her own knowledge.

Pagsuyoin’s NSF CAREER award, which provided $513,000 over five years, also sees her working on the impact of drug abuse on the aquatic ecosystem. She says this is a natural evolution from her research for a doctorate in environmental and civil engineering, which examined aquatic pollutants that disrupt hormones. Many scientists took up that work, and Pagsuyoin realized that the cutting edge of this research was on the effects of synthetic illicit drugs, which have not yet been studied much.

Her NSF-funded project has her working with graduate students to discover how these synthetic drugs break down in aquatic ecosystems and how they affect freshwater microorganisms. Research on fish will come in a separate study.

Protecting the Aquaculture Industry and Coastal Communities

During the pandemic, Pagsuyoin collaborated with Luo on a low-cost, wireless biosensor that detects the COVID-19 virus in wastewater.

Today, Luo is the lead investigator on a three-year, $1 million NSF-funded project, called BioSPACE, that expands the capabilities of that biosensor to work in new environments and on new pathogens. Pagsuyoin is working with Luo as one of the team’s co-principal investigators.

Luo’s team interviewed 130 aquaculturists—people who raise shrimp, oysters and other seafood—to find out which pathogens pose the biggest threats to their businesses. “We really got to know the oyster farmers in the Northeast,” Luo says. As a result of those conversations, the researchers are focusing on creating biosensors for two bacteria, Vibrio and Pseudomonas.

The project does not just concern the health of shellfish, Luo says: “It also involves human health, because oysters are often consumed raw.” If those oysters are contaminated with Vibrio, it can result in an illness that is often mild but can also be fatal.

One of the challenges for Luo’s team is adapting a biosensor that works in wastewater-to-saltwater conditions.

“This is critical in safeguarding public health, particularly in vulnerable coastal areas that provide communities with food, recreation and protection from storms,” says Luo.

Luo and Pagsuyoin believe their research can be applied to numerous aquatic environments. Whether it is water from the Merrimack River flowing through the UML campus, a wastewater treatment plant in Lowell or across the globe, or the briny waters of an oyster farm, the researchers are creating new techniques and technologies to understand and protect our water, our health and the environment.