Microbiome May Hold Clues That Could Revolutionize Diagnosis and Treatment

10/19/2023

By Karen Angelo

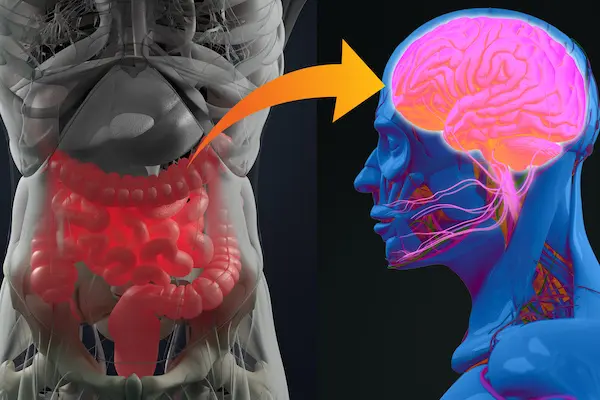

What’s the connection between the trillions of microorganisms thriving in our gastrointestinal tracts and the health of our brains?

Researchers in the Zuckerberg College of Health Sciences are exploring how the gut microbiome contributes to the risk of Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s diseases. This research could lead to earlier detection and new treatments for people with those diseases, which impact millions of people in the United States and around the world.

In a new study published in the Annals of Neurology, Assoc. Prof. of Public Health Natalia Palacios found that healthy, anti-inflammatory bacteria were less abundant among people who were diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease. The results of the study, which was funded by a $2.1 million grant by the National Institutes of Health, highlight the critical role of the gut-brain axis, a two-way communication system that connects the gastrointestinal tract and the central nervous system.

They found a consistently lower abundance of certain types of anti-inflammatory, anaerobic bacteria in people with Parkinson’s disease. This change was also noticeable among study participants who experienced early signs of Parkinson’s disease, which can predate the onset of the classic motor symptoms by many years.

“These species of bacteria are known for their role in reducing inflammation in the gut,” says Palacios. “This depletion supports a potential link between gut inflammation and Parkinson’s disease (PD). The fact that we see these changes before a PD diagnosis suggests that, in the future, the gut microbiome may serve as a biomarker for identifying the earliest phases of PD. This has the potential to revolutionize the diagnosis and treatment, as early detection is often key to developing new therapies.”

The Gut-Brain Axis and Alzheimer’s Disease

Palacios and Prof. Katherine Tucker of the Department of Biomedical and Nutritional Sciences are now turning their attention to new research that examines the connection between the microbiome and Alzheimer’s disease. The brain disorder slowly destroys memory, thinking skills and, eventually, the ability to carry out the simplest tasks, according to the National Institute on Aging.

“Puerto Ricans, who suffer from health and social disparities, have a 50% greater risk of Alzheimer’s disease compared with the general population,” says Tucker. “We have been conducting cognitive assessments and measuring the diets and health outcomes in this cohort for almost 20 years, so we have a lot of data for this new study.”

With updated cognitive assessments and the analysis of MRI brain scans and blood and stool samples, the research team will identify the gut composition in each participant, the function of each species of bacteria, and any harmful molecules that could cause disruption in the brain.

The research team is conducting a “multi-omic” study, a comprehensive approach that simultaneously analyzes multiple types of biological data, which provides insights into how these interact with each other.

“The results of our study could lead to novel biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease, as well as a better understanding of what causes the disease,” Palacios says.

What the researchers learn from the study could impact millions of people: More than 6 million Americans are living with the brain disorder, according to the Alzheimer’s Association. By 2050, that number is projected to grow to 12.7 million.

We Are What We Eat

The increased understanding of the role of the gut microbiome in overall health raises the question: What can we do to improve our gut health?

“Eating a healthier diet is the best medicine,” says Tucker.

A key to a healthy gut is feeding the good bacteria in our microbiome, and the best way to do that is to add probiotic foods like yogurt, tempeh, miso and kimchi, which directly provide good strains of bacteria. Prebiotic fiber-rich foods include whole grains like oatmeal, farro and barley, legumes, and high-fiber vegetables and fruits such as asparagus, onions, apples and berries.

“Think of your body as a little factory where the good bacteria like to eat fiber,” says Tucker. “When you feed bacteria fiber, it produces good things such as short-chain fatty acids, which we know help to fight inflammation and boost the immune system.”

A high-fiber diet can also help reduce the risks of obesity, type 2 diabetes and brain diseases, she adds.

Tucker says limiting processed and fried foods and products containing sugar and white flour can also help. Such foods feed the bad bacteria, allowing them to multiply and interfere with the intestinal barrier and the blood-brain barrier, the tight layer of cells that protects the brain from harmful substances and maintains its delicate chemical balance.

“While all of this research is exploding in the world of the microbiome and health, we know that a healthy diet improves health outcomes in profound ways,” says Tucker. “Don’t wait to start eating healthy foods. You really are what you eat.”