Center for Lowell History Designated ‘Underground Railroad Research Facility’

Image by Center for Lowell History

Image by Center for Lowell History

Several of the "Untold Lowell Stories" are about members of the Lew family, who lived in this home at 89 Mt. Hope Street that was built in 1846 by Adrastus and Elizabeth Lew.

05/27/2021

By Ed Brennen

When Congress passed the Fugitive Slave Act in 1850, making it a crime to aid “Freedom Seekers,” Booth briefly fled to Canada. But in 1851, Boott Cotton Mills Agent (CEO) Linus Child raised $750 from the Lowell community to purchase Booth’s freedom.

That’s just one example of the anti-slavery and abolitionist movements that existed in Lowell two centuries ago — movements that are chronicled in “Untold Lowell Stories: Black History,” an online research guide recently published by the UMass Lowell Library’s Center for Lowell History.

The collection of 32 stories, which includes Martin Luther King Jr.’s visit to Lowell’s First United Baptist Church in 1953 and biographies of those who supported freedom seekers like Booth, are the work of Martha Mayo, who retired as the Center for Lowell History’s director in 2015.

“I’d gathered a lot of the resources over the years,” says Mayo, who in February began posting one story a day on her personal Facebook page in honor of Black History Month.

Image by Kevin Harkins

Image by Kevin Harkins

Martha Mayo, former director of the Center for Lowell History, began posting stories about the city's anti-slavery and abolitionist movements to Facebook during Black History Month.

As the “likes” and “shares” started piling up, several readers suggested that Mayo curate the stories into one collection. So she asked Tony Sampas, the university’s archivist and special projects manager, if he could turn her posts into an online research guide, or LibGuide. Sampas gladly accepted the task.

“Nobody knows the material like she does. This is mostly Martha and her 30 years of experience, with the library giving it a voice and a place to be seen,” says Sampas, who dug up high-resolution images to accompany Mayo’s stories.

The collection builds on the Center for Lowell History’s designation in March 2020 as an Underground Railroad Research Facility by the National Park Service’s National Underground Railroad Network to Freedom program.

Mayo, who submitted the center’s application in 2019, says the designation is important because it shows another side to Lowell’s “complex” history as a center of cotton textile production.

“If you just assume that Lowell is a pro-Southern city dependent on cotton and slavery, it’s hard to recognize or understand that it could also be an anti-slavery city and an Underground Railroad site. The stories are in conflict,” she says. “But when you learn about the people who were living in this city in the 1840s and ’50s, it’s understandable.”

Image by Center for Lowell History

Image by Center for Lowell History

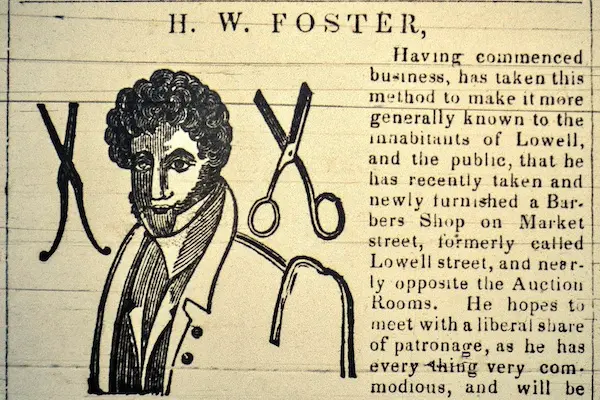

Barbershops, such as this one in Lowell owned by Horatio W. Foster, were often gathering places for Black and white abolitionists.

For those who want to see where members of the city’s small Black community lived and worked and where the anti-slavery societies, churches and abolition newspapers once stood, Mayo and Sampas also created two maps for self-guided walking tours of the Downtown Lowell Anti-Slavery and Underground Railroad District. The maps feature descriptions and links to 33 sites, including Old City Hall, where Frederick Douglass spoke out against slavery in the 1840s.

“The tours provide a fuller historic context,” Sampas says. “Some of the buildings don’t exist anymore — they’re just an empty lot.”

To tell the “untold” stories, Mayo had to look beyond the traditional history books, digging up scraps of information from newspaper archives and personal letters and diaries.

“They were not already crafted and published; they had to be put together bit by bit,” she says.

Sampas enlisted the help of several work-study students to inventory the many folders containing Mayo’s research, making the collection more accessible for scholars and researchers.

Image by Center for Lowell History

Image by Center for Lowell History

Lowell native Harry Haskell "Bucky" Lew, second row far right, became the country's first Black professional basketball player when he joined the Pawtucketville Athletic Club in 1902.

Evan Dupuis, a rising sophomore electrical engineering major, says it’s gratifying that future generations of students will have access to the research that he helped to catalogue.

"It's amazing that I get to work with documents that contain the history of where I live and go to school,” he says.

Chloe Lewis, a rising sophomore chemical engineering major, was “shocked” to see how much research Mayo had amassed, “which was interesting to read in between relabeling the folders,” she says.

Last summer, around the centennial of the 19th Amendment, Mayo also posted stories on Facebook about women in Lowell who were involved in the fight for voting rights. Those stories might be her next LibGuide project, she says.

“It’s fun to do. COVID put a crimp on going out much, so I had time on my hands,” she says, adding that retirement isn’t a time to slow down. “Aren’t you supposed to be busy?”