New Processing Lab Allows for More Surveillance Tests, Gives Students Real-world Experience

Image by Ed Brennen

Image by Ed Brennen

03/10/2021

By Ed Brennen

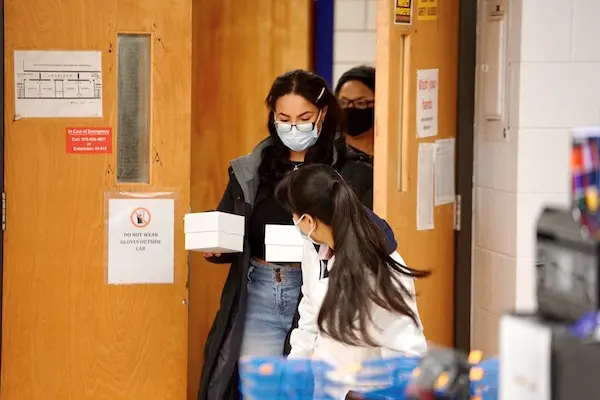

There’s a knock on the door at Room 203 of the Olney Science Center.Biotechnologygraduate student Surbhi Mavi has been waiting for the visitors and springs to her feet to greet them. When she opens the door, two students hand Mavi three small, white boxes.

Inside the boxes are about 150 sealed vials. They contain the nasal swabs collected that morning from students, faculty and staff at University Crossing as part of UMass Lowell’s COVID-19 surveillance testing program.

Mavi andclinical laboratory sciencesmajor Brendan Leung carefully open the boxes and begin scanning the barcodes on each vial into a computer system — the important first step in a high-tech testing process for the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus that will take the next several hours.

Opened this semester under the direction ofMatthew Gage, an associate professor of chemistry in theKennedy College of Sciences, UML’s in-house COVID-19 testing lab is capable of processing up to 700 swabs a day.

The university previously sent all of its test swabs to the Broad Institute in Cambridge, Massachusetts, an MIT-Harvard collaborative that processes hundreds of thousands of COVID-19 tests from across the region daily. Some UML tests, such as those for student-athletes, are still sent to Cambridge, but most swabs now remain on campus.

By processing swabs at Olney — using the same “gold standard” polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test that is performed by the Broad Institute — the university has been able to expand its surveillance testing of asymptomatic students, faculty and staff who are on campus this semester.

“The work that Matthew and his team are doing has been critical to keeping the university community safer,” says Vice Chancellor for Research and InnovationJulie Chen, who leads UML’s testing efforts.

Image by Ed Brennen

Image by Ed Brennen

‘We Could Do This’

Gage’s involvement with the lab is a byproduct of his research on the potential genetic factors behind the severity of COVID-19 symptoms. He and Jack Lepine, of the UML Next Generation Sequencing and Genomics Lab, lead a team that’s looking at ribonucleic acid (RNA) sequencing of patient samples for clues as to why some people get sick from the virus and others do not.

“As we were getting that off the ground, I started to hear about other schools, such as the University of Arizona, setting up their own testing protocols,” says Gage, who reached out to Chen and Vice Provost for Academic AffairsJulie Nashabout doing the same at UML.

“We’ve got the ability, the technology and the workforce here on campus that we could do this,” he told them.

Given the green light, Gage and Lepine spent the fall validating testing protocols and stockpiling supplies such as chemical reagents, test tubes, disposable pipettes and gloves. They also gathered equipment, including two thermal cyclers (used in the PCR process to amplify segments of DNA) from another UML research facility; water baths from various labs across campus; and two robots that the university purchased to help automate the testing procedure.

They also began assembling a team to work in the lab. Alum Mary Beth Fletcher ’20, who earned a master’s degree in clinical lab sciences last May and works as a process development associate at the Broad Institute, was hired to co-manage the UML lab along with Broad colleague Austin Boesch, a Harvard graduate student.

“I feel very fortunate to know how to do something to help with the pandemic. Accurate testing is one of the things we need in order to respond effectively to COVID-19,” says Fletcher, who splits her time between both labs. “When I added the job at UML, I was glad to be helping the university community with testing — and also glad to be teaching students these skills that will be needed going forward.”

Image by Ed Brennen

Image by Ed Brennen

Nearly 20 students have been hired and trained to work in the lab so far, including several from the clinical lab sciences master’s program. One of the program’s students, Anh Ngo ’20, is earning three credits for her work in the lab as part of a course that was created in collaboration with Master’s Program DirectorSuzanne Moore.

“We’ve got degree programs training students to go work in hospital labs, so why not leverage that as a resource for this?” Gage says. “It’s exciting to see what the students are capable of. This is a very different experience than in a teaching lab.”

Leung, who is halfway through his five-year clinical lab sciences bachelor’s-to-master’s program, applied to work in the testing lab after being laid off from his job as a campus shuttle bus driver last spring.

“I feel like I’m making a difference with this work, and what I’m learning about PCR testing is going to help me a lot in my career path,” says Leung, a native of Framingham, Massachusetts, who works in the lab four days a week.

Pooling Their Efforts

After the vials containing the nasal swabs are scanned into the computer, each one is transferred to a tube that is preloaded with one milliliter of phosphate-buffered saline solution and heated to 65 degrees Celsius (149 degrees Fahrenheit) for 30 minutes.

“We have to make sure we’ve inactivated the virus enough that if someone is accidentally exposed, they wouldn’t become infected,” Gage says. “But there is a balance because we also don’t want to destroy the RNA that we’re looking for.”

A robot then collects solution from four test samples and pools them into one combined sample. If the combined sample tests positive, the team then goes back to the original four samples and tests them individually to find out which one (or more) is positive.

Image by Ed Brennen

Image by Ed Brennen

“Given the low level of infection we have on campus right now (0.21% as of early March), it’s an effective way to minimize the amount of work and maximize the amount of results,” Gage explains.

The pooled solutions, lined up neatly in a 96-well plate system, are then run through an RNA extraction process. From there, it’s on to the thermal cycler for the PCR reaction testing — a complex process that creates a fluorescent light signal that is measured by the computer.

“It recognizes two sections of the viral genome and will amplify that. If we see that amplification, it indicates there’s virus present,” says Gage, who adds that PCR tests appear to be able to detect COVID-19 variants.

If the lab comes up with a positive test, that individual is instructed to be retested through the Broad Institute to confirm their diagnosis.

Gage, whose lab is processing more than 2,000 tests per week, says everyone is “learning on the fly” when it comes to the virus. He’s proud to see UML contributing to the scientific community’s unprecedented collaboration over the past year.

“As a university, the ability to pivot and adapt has been phenomenal,” he says.

And for Mavi, a native of New Delhi, India, who earned her bachelor of science in biology last spring, it’s an opportunity to apply what she’s learning in class to a real-world health crisis.

“I want to go to medical school, so this opportunity is just an amazing experience," she says. "I feel very proud to be a part of it.”