University to Honor First Black Pro Basketball Player and Former Lowell Textile Coach

Image by Center for Lowell History

Image by Center for Lowell History

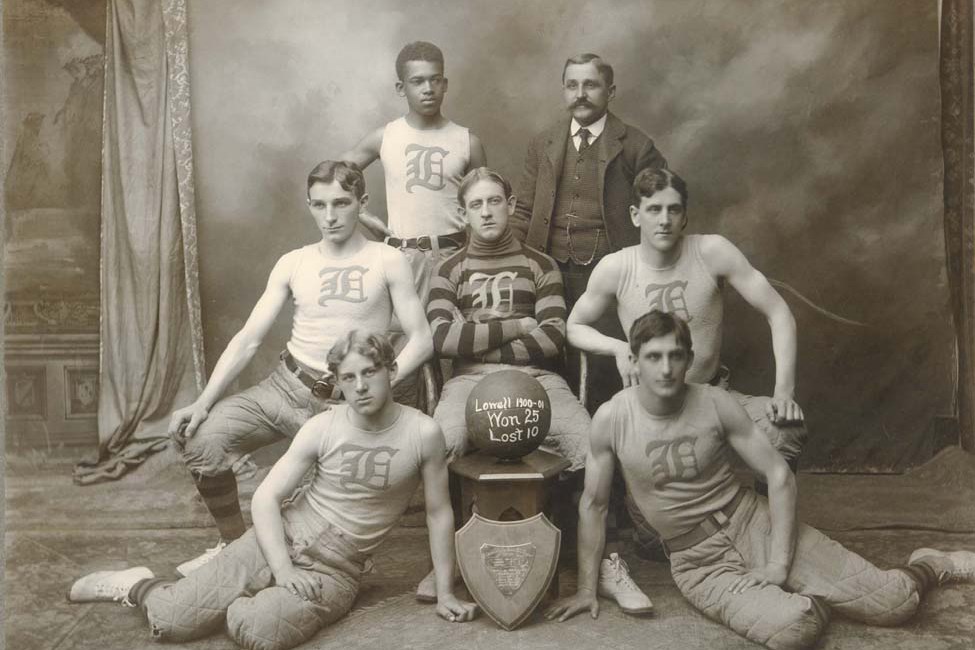

The university will honor Lowell native Bucky Lew, back left, during the men's basketball game on Feb. 22 at Costello Athletic Center. Lew, seen here with the 1900-01 Lowell YMCA basketball team, became the first Black professional basketball player with Pawtucketville Athletic Club. He coached Lowell Textile School in 1922.

02/12/2024

By Ed Brennen

Forty-five years before Jackie Robinson broke Major League Baseball’s color barrier, Lowell native Harry “Bucky” Lew became the first Black professional basketball player.

While Robinson is remembered as one of the most important figures of the 20th century, Lew is but a historical footnote.

That’s starting to change, however, thanks in part to a UMass Lowell alum.

In 1902, an 18-year-old Lew made history when he took the court with Lowell’s Pawtucketville Athletic Club of the New England Basketball League, becoming the first Black professional player in the country.

Twenty years later, Lew made history again when he became basketball coach at Lowell Textile School (now UMass Lowell), making him the first Black coach of an integrated college basketball team.

As part of Black History Month, the university will honor Lew’s legacy during the UML men’s basketball game on Feb. 22 at 6:30 p.m. at Costello Athletic Center. One of Lew’s granddaughters, Wendy Johnson, plans to be there. So does English alum Chris Boucher ’93, who last year published a book about Lew, “The Original Bucky Lew.”

Image by courtesy

Image by courtesy

Wendy Johnson has fond memories of her grandfather Bucky Lew as a child in Springfield, Massachusetts, including this photo from her second birthday.

One of her favorite memories is of their Saturday morning walks together to the bakery for sugar cookies, followed by a visit to the Six Corners Cafe.

“He’d put me up on a barstool and I’d have my Coke. And then it was always, ‘You're not going to tell Nana where we were,’” Johnson recalls with a smile.

But Lew rarely talked about his basketball days, which began at the Lowell YMCA in 1898 — just seven years after James Naismith invented the game in Springfield.

“I don’t know if he was being shy, or if he was just happy that he’d been able to play,” Johnson says. “Sometimes, he told us how he got called names and took punches, and he took it in stride because he loved the game. That was one thing he did tell me to do: When you get something you like, stick to it, no matter how hard it might be.”

Lew is descended from a long line of history-makers. His great-great-grandfather, Barzillai Lew, was born a free Black man in Groton, Massachusetts; he served in the Revolutionary War and played the fife at the Battle of Bunker Hill in 1775. One of Barzillai’s daughters, Lucy Lew, was a civil rights activist in Boston who helped integrate the city’s schools in 1855.

Image by Wendy Johnson

Image by Wendy Johnson

Wendy Johnson sits on her grandfather Bucky Lew's lap as family members in Springfield celebrate her second birthday.

Bucky Lew’s grandparents, Adrastus Lew and Elizabeth Freeman, built a home at 89 Mount Hope St. in Lowell’s Pawtucketville neighborhood, just two blocks from UML’s North Campus, that was a stop on the Underground Railroad. His father, William, was a delegate to the 1891 Equal Rights Convention in Boston.

Bucky Lew was the oldest of four children. In 1914, his sisters Teresa Garland Lew and Marion Scott Lew became the first African Americans to graduate from the Lowell Normal School (now UMass Lowell). Teresa became the first Black teacher in Lowell public schools and the first Black person — and woman —- to earn a law degree from Portia Law School in Boston (now New England School of Law).

His brother, Gerard Nelson Lew, moved to Chicago and co-founded the DuSable Museum, the oldest museum in the country dedicated to Black history, culture and art. One of its artifacts is the powder horn that Barzillai played in the American Revolution.

“The Lew family was in Lowell before Lowell was Lowell,” notes Boucher, who grew up in the same Pawtucketville neighborhood as the Lews — which was part of Dracut until 1874.

Image by Ed Brennen

Image by Ed Brennen

English alum Chris Boucher '93, author of "The Original Bucky Lew," looks at the original basketball court lines at Southwick Hall, where Lew coached in 1922.

“I was stunned. Even though I’m a basketball fan, I really didn’t know anything about the sport between its invention in 1891 and the creation of the NBA in the late ’40s. I wanted to learn as much as I could,” says Boucher, who headed to the UMass Lowell Center for Lowell History to dig into Lew’s story.

To Boucher’s surprise, little had been written about him.

“There were a few footnotes about his accomplishments, but not a lot of detail,” he says. “When I saw the depth of his career and all that he accomplished — not only as a player and coach, but also as a referee and franchise owner — I knew this could be a book.”

Image by Chris Boucher

Image by Chris Boucher

Wendy Johnson, left, and her daughter Kiah visit Lew Family Square in Lowell, which is dedicated in their family's honor.

“It became an obsession of sorts,” says Boucher, who spent three to four hours a day on the book — on top of his day job as an instructional designer at Imprivata, a software company.

One of the people he interviewed was UML Professor Emeritus of English Gerard O’Connor, whose father Dan had played with Lew. O’Connor passed away in December at the age of 88.

Boucher also visited some of the New England towns where Lew played with semi-pro teams after the New England Basketball League folded in 1905. On a recent visit to UML, Boucher saw the former Lowell Textile basketball court on the fourth floor of Southwick Hall, where Lew coached. The space was recently converted to the Lowell Advanced Robotics Initiative (LARI) Laboratory, but some of the original basketball court lines are still visible on the hardwood floors.

Boucher also donated some of his book’s proceeds to help fund a plaque in Bucky Lew’s honor at the Lowell YMCA. Johnson attended the plaque’s unveiling last November with her daughter, Kiah.

“It was fantastic,” says Johnson, who works as an X-ray tech and lives in Milton, Massachusetts. “There’s so much in our family history, and I tell my daughter you have to learn as much as you can and pass things along.”

Image by Ed Brennen

Image by Ed Brennen

Wendy Johnson didn't pursue basketball like her grandfather Bucky Lew, but she treasures the life lessons that he passed down.

“It’s nice to dust off his memory a little bit and see that he still has living family members who care and want him to get that recognition,” says Boucher, who is also helping to organize a Juneteenth celebration in Lew’s honor this summer at Lowell’s Muldoon Park.

Despite his place in basketball history, Lew has yet to be inducted into the Basketball Hall of Fame in Springfield.

“I think they don’t know the extent of his accomplishments,” says Boucher, who hopes the recognition that Lew is starting to receive in his hometown of Lowell can help change that.

“It would be wonderful if we could get a little something about him in the Hall of Fame,” Johnson says. “I’m glad that Chris took the time to write the book and to follow through on the plaque. And to see what UMass Lowell is doing for us, it’s just wonderful.”